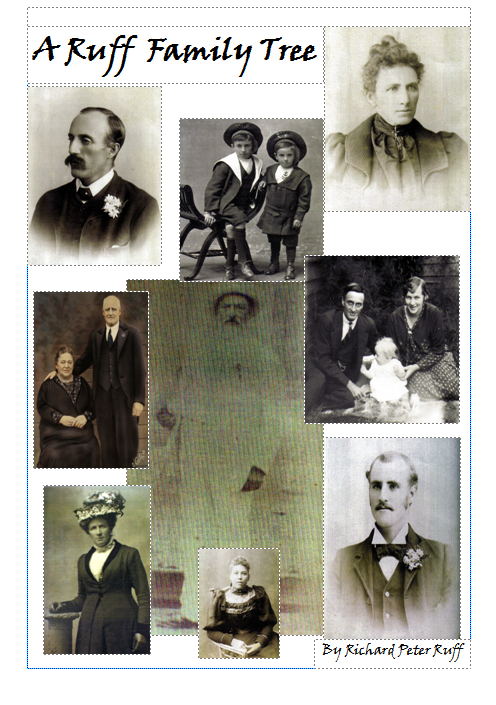

Distant Shores: The Odyssey of Abraham Ruff

Prologue: Shadows of Zurich

On Christmas Day, 1812, Abraham Ruff was born into a Zurich blanketed by snow, the air sharp with the scent of pine and chimney smoke. Switzerland then was a patchwork of cantons, each clinging to its own traditions, languages, and loyalties. Life was slow and deliberate, church bells tolled the hours, and families gathered around hearths to fend off the Alpine chill. For a boy like Abraham, growing up meant learning the rhythms of a cobblestoned city: the clatter of wooden carts, the murmur of German, French, and Italian dialects, and the distant clang of blacksmiths shaping a world on the brink. The early 19th century offered little luxury; most lived modestly, their days dictated by seasons and faith. Yet, beneath this quiet, tensions simmered, Catholic and Protestant rivalries that would soon erupt, shaping the man Abraham would become.

Chapter 1: The Sonderbund’s Shadow

By 1847, Zurich was a city taut with unease. The Sonderbund War loomed, splitting Switzerland between Catholic defenders and Protestant reformers. For Abraham, now 34, life was a blend of labor and risk. He likely lived in a narrow, timber-framed house, its walls echoing with the shouts of political rallies outside. The air carried the tang of gunpowder and the sour sweat of fear as militias drilled in the streets. Markets buzzed with whispered conspiracies, and taverns overflowed with men debating over mugs of dark ale. Abraham backed the Catholic Sonderbund, he felt the weight of dwindling coins as he funded their cause. When war broke in November, cannon fire rumbled through the valleys, and blood stained the snow. Defeat came swiftly, and with it, the sting of betrayal and loss, now being chased for murder meant he had only one option, to flee. Fleeing meant abandoning a life of woolen coats and hearty stews for the unknown, his breath fogging in the frigid night as he slipped away alone.

Chapter 2: London’s Tempest

London in late 1847 was a beast of a city, its streets choked with coal smoke and the cries of costermongers. Abraham arrived amid the din of horse hooves and factory whistles, the Thames a sluggish ribbon of filth. Life here was raw, tenements sagged under the weight of families crammed into damp rooms, their days spent dodging cholera and scavenging for bread. For a newcomer like Abraham, survival meant navigating a labyrinth of accents and alleyways, his Swiss roots masked by a cautious tongue. The winter bit hard, with fog so thick it swallowed gaslights, and hunger gnawed at the poor. By March 1848, the Trafalgar Square Riots ignited this tinderbox. The square pulsed with the heat of bodies and the crack of breaking wood, the air thick with dust and defiance. Abraham, while walking was caught in the melee, he felt the adrenaline of rebellion, destruction by the youth at hand. Arrested, he endured the dank chill of a cell, the clank of iron bars a stark reminder of his fragility. Released, after the judge realized he could barely speak a word of English, or so he came across. Abraham soon after met and married Ann Gorman Eveson/Erison on 13th February 1849, their modest wedding a flicker of warmth amid London’s gray sprawl, her Irish lilt a balm to his restless soul. Ann became pregnant and gave birth to Louis Andrew Ruff on 28 May 1851 at 11 Pickard St, Finsbury.

Chapter 3: The Voyage of the Lord Delaval to Australia

The Lord Delaval was a wooden sailing ship and a fragile hope, its decks groaning under 700 tons of cargo and dreams. In September 1852, Abraham, Ann, and infant Louis stepped aboard, the salt air stinging their faces as England faded. Life at sea was a trial of endurance, the cabins reeked of unwashed bodies and tar, while storms tossed the ship like a toy, the horizon a relentless tease. Steerage passengers like them cooked meager meals on swaying stoves, the taste of salt pork and hardtack a daily monotony. Waves roared, and nights were pierced by the cries of the sick or the wails of a child, Louis, frail in Ann’s arms, his arrival to Australia not marked. Sophia Knight, a sprightly 10-year-old, darted among the rigging, her laughter a rare light. For Abraham, the journey was a gamble, his identity rewritten on the manifest as a 32 year old German tallow melter, along with his German wife Ann, each day a test of will against the vast, indifferent ocean. Arrival at Port Phillip on the 27th of February 1853 brought relief but no rest; the wagon to Melbourne jolted over rutted tracks, dust coating their throats as they clung to their new world.

Chapter 4: Melbourne’s Candle King

Melbourne in 1853 was a raw frontier, its streets a muddy churn of gold-rush dreamers and opportunists. Abraham soon was established at Queensbury Street, Hotham (North Melbourne), their home buzzed with the hiss of boiling tallow and the flicker of candlelight, the air heavy with grease and ambition. Life here was gritty, wooden shacks leaned against brick factories, and the Yarra River stank of refuse. Summers scorched, winters soaked, and flies plagued every meal of mutton and damper. They maintained their friendship with the Knight’s during this time, Sophia, now 18. For Ann, it was a battle to keep going after Louis's death, amid the soot, her hands chapped from the harsh life. Abraham thrived, his soap and candles a lifeline for a city craving order, though court fines for reckless horses hinted at his impatience with colonial rules. Ann’s death in 1860 left the house silent, the bronchitis that took her a cruel echo of London’s dampness. Sophia consoled Abraham during this time, and soon became his bride, bringing new energy, her youth clashing with her parents’ scowls. Sophia and Abraham had early losses, Sophia and Frederick, cast a pall. By 1863, young Abraham’s cries filled the factory, a symbol of endurance in a land that demanded grit. A shipment of Abraham’s candles that he was exporting sank in Port Phillip Bay, unfortunately, the insurance didn’t take effect until the ship was outside the Heads. With this financial blow, Abraham looked at alternative ways of making income, distilling.

Chapter 5: The Distiller’s Gambit

By 1868, Melbourne had grown into a bustling hub, its streets lined with gas lamps and the clatter of horse-drawn trams. Abraham’s factory was a hive of heat and hustle, the tang of spirits mingling with tallow’s musk as he distilled in secret. Life was a tightrope, prosperity teetered against the law’s watchful eye, and neighbors grumbled at the stench wafting from his yard. Sophia managed a growing brood, her days a blur of diapers and dough, the children’s laughter drowned by the city’s roar. The police raid on May 8 was a jolt, boots thudded on floorboards, and the still in full working order with some spirits betrayed him. Arrested, Abraham shivered in the lockup’s dank chill, illness gnawing at his bones until he was hospitalized. The community held a fundraising concert to pay the fine and set him free. Once again, in trouble with the law, it was time to move on. Sale beckoned—a quieter canvas for his restless spirit, the wagon ride there a dusty trek through eucalyptus-scented wilds.

Chapter 6: Sale’s Maverick

Sale in 1869 was a speck of civilization, its wooden storefronts dwarfed by endless plains. Abraham’s soap vats bubbled anew, the air thick with lye and promise, while Sophia stitched clothes by lamplight, her hands rough from toil. Abraham sold his soap making recipe for 100 pounds to J. Kitchen & Sons who were buying up all the smaller soap and candle manufacturers of Victoria at the time, this became the famous Velvet Soap. Life was simpler but harsh, dust storms coated everything, and summers baked the earth to iron. The family grew, each child a thread in their tapestry, though courtrooms remained a stage for Abraham’s defiance: unpaid rates, pilfered timber, petty debts. The Notre Dame de Sion Convent Garden offered respite, as he spoke French to the nuns in their native tongue, their habits rustling like whispers of Zurich. Abraham and Sophia adopted Arthur and Solomon while raising their own 8 children, which tied them to Sale, their young voices an echo of his own lost boys. Arthur died while fighting in Gallipoli in 1915. Chapter 7: The Hounds and the Legacy By the 1890s, Sale had settled into a rhythm, its streets alive with the clop of hooves and the chatter of settlers. Abraham, now stooped and gray, tended the convent’s roses, the scent a fleeting comfort against age’s ache. Nights were crisp, the sky a vast quilt of stars, until the greyhounds’ attack, a blur of teeth and terror, felled him. Death came gently on December 19, 1898, his breath fading in a room warmed by Sophia’s care. She endured until 1911, her final days shadowed by a redback spider’s bite, the woodpile a silent witness to her strength.

Chapter 7: The Hounds and Redback Spider

By the 1890s, Sale had settled into a rhythm, its streets alive with the clop of hooves and the chatter of settlers. Abraham, now stooped and gray, tended the convent’s roses, the scent a fleeting comfort against age’s ache. Nights were crisp, the sky a vast quilt of stars, until the pack of greyhounds’ attacked, a blur of teeth and terror, felled him. Death came gently on December 19, 1898, his breath fading in a room warmed by Sophia’s care. She endured until 1911, her final days shadowed by a redback spider’s bite, the woodpile a silent witness to her strength. Abraham’s life was a flame that flickered across continents, fueled by courage and cunning. From Zurich’s Sonderbund War, to London’s Trafalgar Square Riots to Melbourne’s gritty dawn, he carved a path through a world in continual change, leaving a legacy of tales that inspired his kin to chase their own distant shores.

Chapter 8: A Legacy in Flour and Flame

The legacy of Abraham Ruff, the restless wanderer from Zurich, did not fade with his passing in 1898, nor with Sophia’s in 1911. It lived on in their children, a brood of ten, though marked by the early losses of Sophia Emily Agnes and Frederick Edward, who carried the family name through the rugged landscapes of Gippsland. The adopted sons, Arthur Abernethy and Solomon Perdon, added their own threads to the tapestry, though Arthur’s life ended in the muddy trenches of Gallipoli in 1915, and Solomon’s path blurred into the annals of Hotham’s council records. But it was the eldest surviving son, Abraham Ruff Jr., born in 1863, who would etch his own mark on the world, a man of dough and fire, whose life mirrored his father’s grit in a new era. Sale in the late 19th century was a town of dust and determination, its streets lined with weatherboard shops and the scent of eucalyptus heavy in the air. Young Abraham, at just three years old, had jolted into this world on a wagon from Port Albert, the creak of wheels and the tang of salt air his earliest memories. The family’s modest home on York Street hummed with the clatter of Sophia’s cooking and the laughter of siblings—Henry, Edward, Bertha, Rosa Bona, Frederick, and Ida Violet joining the fold over the years. Education was a sparse affair, a few hours in a drafty schoolroom where slates scratched with lessons, but Abraham’s true learning came from the land and the people. He fished in the Thomson River, his bare feet sinking into the muddy banks, and roller-skated on makeshift rinks as he twirled with a grace that would later make him an expert dancer.

At 15, in 1878, Abraham turned his hands to baking, apprenticing under a gruff Sale baker whose ovens roared with the heat of a new day. The work was grueling, kneading dough until his arms ached, the air thick with flour dust and the yeasty tang of rising bread. Sale’s residents, a mix of farmers and shopkeepers, lived on simple fare: damper, mutton, and tea brewed over open fires. Abraham’s bread became a staple, its crusty warmth a comfort in a town where summers scorched and winters brought icy winds off the Gippsland Lakes. By his 20s, he was a master baker, his loaves winning praise at local fairs, their golden tops a testament to his skill.

But life in Sale was not without its perils. On a crisp January morning in 1893, Abraham, now 30, set out fishing with a friend, William Jones. The river, a glassy ribbon winding through the bush, shimmered under the summer sun, its banks alive with the hum of cicadas. The two men rowed a small boat, their laughter echoing over the water, until a sudden lurch overturned their craft. The current seized them, cold and relentless, and Abraham, unable to swim, flailed against the pull. His hands grasped at reeds, the muddy bank a lifeline as he hauled himself ashore, gasping and soaked. William was not so fortunate—his body vanished beneath the surface, a tragedy Abraham reported to the police with a heavy heart, his voice trembling as he recounted the loss.

This brush with death steeled Abraham’s resolve, and he channeled his energy into service. He joined the Sale Fire Brigade, a band of volunteers who battled blazes with leather buckets and sheer will. Fires were a constant threat in Gippsland, where wooden buildings and dry summers conspired to spark disaster. Abraham’s small stature belied his strength—he hauled hoses through choking smoke, his face blackened but his spirit unbowed, earning the respect of his comrades. In 1913, Abraham moved his family to Maffra, a bustling town 20 miles from Sale, after a devastating fire on Christmas Eve tore through Johnson Street. The blaze, fueled by a dry wind, reduced shops from the shire offices to the National Bank to ash, the crackle of flames and the cries of onlookers haunting the night. Abraham, who had cycled the distance between Sale and Maffra each weekend to work, a grueling ride over rutted tracks, the sun beating down or rain soaking his coat, saw the need for action. He founded the Maffra Fire Brigade, becoming its first captain, a role that fit him like a glove. Under his leadership, the brigade drilled with military precision, their boots pounding the earth as they practiced with hand-pumped engines, the tang of smoke a constant reminder of their purpose. Abraham’s baking career flourished alongside his civic duties. His bread, awarded for its quality during the Great War, fed soldiers and families alike, its hearty texture a small comfort amid the rationing and grief of 1914-1918. He baked in Sale, Maffra, Stratford, Bunyip, and Melbourne, each oven a new chapter in a life of movement.

At home, he danced with his wife, Elizabeth Mary Monk, whom he married in Sale, their steps a waltz of joy in a parlor lit by kerosene lamps. They built a house opposite the Agricultural School Farm in Sale, its verandah a perch for watching the world go by, until the move to Maffra in 1913. Abraham’s passions; shooting, fishing, reading, music, filled his days, his teetotaler’s clarity and non-smoker’s vigor a testament to his disciplined nature. Yet loss shadowed his later years. Elizabeth’s death in 1942, after a life shared in laughter and labor, left Abraham hollow, the house in Maffra too quiet without her humming. The deaths of two sons, Edward and Cyril, the latter’s unexpected passing in 1951 a crushing blow, sapped his strength.

By April 1953, as he lay in the Gippsland Base Hospital in Sale, Abraham’s 90 years weighed heavy. His once-steady hands trembled, and his breath came in shallow gasps, but his mind drifted to the river, the bakery, the fire brigade, moments of purpose that defined him. He passed on April 8, surrounded by the whispers of nurses and the distant toll of a church bell, leaving behind sons Will and Theo, daughters Alma and Renee, 16 grandchildren, and 28 great-grandchildren. His siblings, Edward, Henry, Frederick, Sophie, Bertha, and Bona—mourned a brother whose life had burned as brightly as their father’s, while Ida, who predeceased him, waited in memory. The funeral at St. Mary’s Catholic Church in Maffra on April 12 was a quiet affair, the pews filled with family and townsfolk, the air heavy with the scent of incense and the weight of farewell. Abraham Ruff Jr. was laid to rest, a man who, like his father, had lived boldly, his hands shaping bread and dousing flames, his heart a beacon for those who followed.

This is for all the Ruff's who want to know more about our ancestor Abraham Ruff who migrated from Switzerland to England and then Australia. If you have any more info or photos you would like added to this site please contact me at rruff13@yahoo.com.au